Lives saved

1

Hunting

Lost

Thunder storm

Kaimanawa Ranges

-39.25°S, 175.9°E

Posted on May 2, 2018 by Glenn

What happened?

Three of us had flown by helicopter into the Department of Conservation landing area on the Waiotaka river in the Kaimanawa Ranges to hunt Sika deer in the roar (mating season).

We had split up for the day, but I was well prepared to hunt alone and come back at night – including provisions such as GPS, headlamp, spare batteries, as well as a paper map and magnetic compass in the event that everything else failed. The camp site was tagged on my GPS and marked on my map.

It is common to come back to camp after dark as the best hunting can be around dawn and dusk when deer come out into clearings to feed. It is something myself and other hunters do often. I guess this story highlights that even when you are prepared and experienced, the New Zealand bush can lead you astray.

I had come across the best spot I had ever seen for Sika in the middle of the day, with obvious scrapes and rutting patches, a wallow, and I got several ‘he-haw’ responses from Sika when I called on the spot. The spot was also only about 30min away from our campsite, with the return trip being fairly steep but all down hill, and no rivers or streams to cross. It seemed obvious to head back to that spot at dusk and try my luck.

I waited for the sun to set but was not rewarded with any deer. Having spent so much time stalking around there earlier in the day, the deer were probably spooked.

I fitted my head lamp – which I keep around my neck so I don’t have to find it in the dark – and to be sure of my trip in the dark I took a GPS reading of where I was. I only had a text based GPS that gives coordinates (no electronic map) – I have to put these coordinates onto my paper map to see where I am, and I could not walk with the GPS as a constant guide.

I then took a compass reading and saw that to head back to the camp on the Waiotaki river, I would have to walk more-or-less directly down hill, with about a 15deg angle to the right.

Unconcerned, I started bashing through the bush with the head lamp on, however I was in reality taking a much shallower angle to the contour than I thought I was.

After about 45min I realised the trip was taking much longer than it should, but heard water ahead so decided to continue. I continued to the water and saw it was a steep drop into a gully where a stream was. The stream was much smaller than the Waiotaki and flowing in the wrong direction. Already guessing what the problem was, I took another GPS reading and looked at the map to confirm my suspicions – I had skewed west hadn’t come to the Waiotaki; I was only half way down the hill and was on the bank of one of the tributaries flowing down the hill to the Waiotaki.

Looking at the map, the tributary came out just west of our camp onto the Waiotaki river. The country I had been coming through had been getting increasingly steep and I knew the land around the Waiotaki where the tributary joined was flat and easy. I now made my mistake – I decided to follow this tributary back to the Waiotaki river. I also thought following the tributary would make navigation in the dark easy.

Bashing down a creek can be the fastest way out of the bush in flatter country. That is not the case in rough country like the Kaimanawa’s where the creeks carve out steep gullies. It was a mistake to go into the creek.

It was a slippery and steep drop down into the creek gully, and I did not want to climb back the way I came. I continued down the creek, but there were several steep drops which I slid down, getting me soaked. At one point, a log jam I was standing on gave way and I took a dunk in a pool. The air temperature was dropping low. I was now getting weaker with cold but I thought if I persisted I would make it out to the easy land.

I came to a point where I could not go further down the creek; the waterfall ahead was too steep. The way back would have been very difficult, the creek was passing through chasms, but the part I was in now was more of a gully. I looked up the gully walls and could not see the top with my head lamp, but there were several healthy trees growing out of the gully walls, so I decided to climb.

The gully walls became a vertical cliff very quickly, but with the trees growing out, still presented the best opportunity to get out of the gully. I was however shaking quite a bit at this point with cold and exertion.

I pulled myself up onto a final tree but looking around, could not see any firm hand grips above me. I would have to drop to go back, but with a headlamp it is easier to look up than see what you are doing going down. Going down wouldn’t get me out anyway. The headlamp was getting weaker and I could not remove the batteries from my pack – I needed to maintain one hand hold in my precarious position and the batteries were wrapped tightly in electrical tape to keep them dry, in my pack on my back. I paused, regained my breath and composure, and decided the best thing to do was to wait until morning and use daylight to assess my situation and choose the safest path off.

To get to this position, I had passed my rifle up to sit on a tree branch before I had pulled myself up. I was able to pick it up with my free hand and fire a single shot to signal my hunting partners back at camp, if they could hear it, that I was OK and to not to come out and find me (this is a commonly known signal). They wouldn’t have been able to help anyway, and the last thing I wanted to do was signal them out into the dark to find me and get into this terrain themselves. I could not have re-loaded to keep signalling as they approached anyway.

A couple of hours passed in which the situation became clearer. I had my cell phone in my front pocket and used the torch on it to survey my surroundings a bit further, and I had convinced myself there was probably no viable way out of here. I was standing on a tree growing out of a crevasse and it was only dubiously taking my weight. I had to keep a hand on the cliff to maintain my balance and I was nodding off being cold and wet. I could sit down and straddle the tree with my back to the cliff, but I thought I would definitely fall asleep in that position and then risked falling. It was getting colder – approaching freezing. I realised that I might not be in a condition in the morning to get off, even with daylight. I finally realised that I had been ‘bluffed’ by the New Zealand bush.

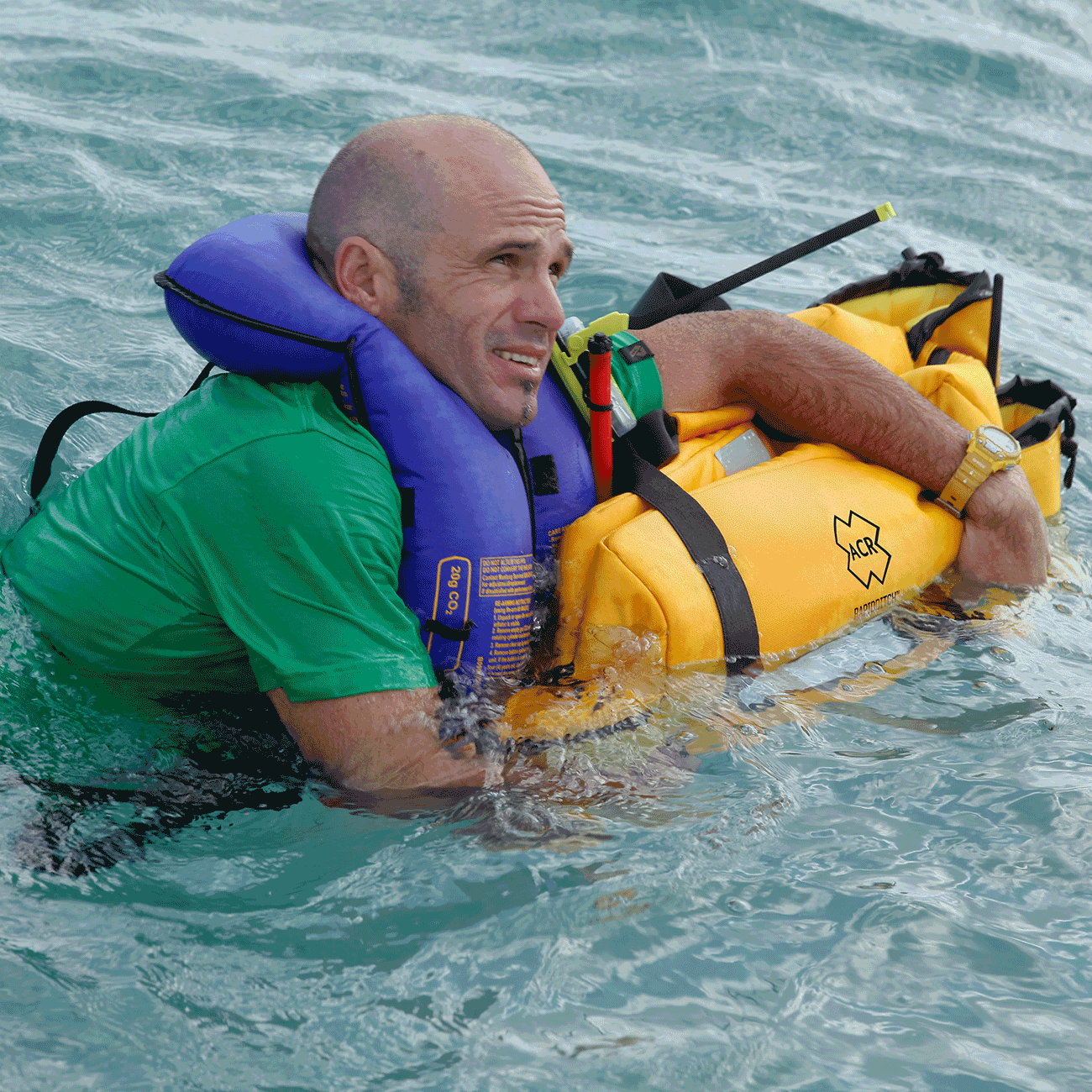

I had the ACR in a front pocket where I would easily get to it with one hand – thinking that if I ever needed it, it would be because of a fall, in which case I might be separated from my pack. That proved to be a saving decision. I still held it for what seemed a very long time, and running through every possible escape route, before I finally pushed the button.

The Greenlea Rescue helicopter came in a straight line to me, they had my exact coordinates from the ACR and could see the strobe from a very long distance. They hovered for some time and illuminated the cliff with their search light. Looking around with their search light going, I couldn’t believe I had climbed up to this point – I wouldn’t have done it in the daylight if I could see what I was doing. Looking up, I could see where the cliff rounded off above me with their search light – about 10m above me – but it may as well have been a mile with nothing to hold onto. I was about 50m up from the gully floor with what looked like a large Kahikatea tree on the gully floor, well below me – these are New Zealand’s tallest trees. To the side the cliff was a featureless face with no holds.

Greenlea couldn’t drop anybody below me where I had come from, and trees precluded a winch, so they flew to the Waiotaki landing area and dropped off the rescuers. They used a GPS with a map display – I am going to buy one of those! – to navigate to the top of the cliff, tie off, and abseil down to me. They fitted me with a harness and assisted me up.

At the top they asked me how I had managed to get down that drop without ropes. They were surprised to learn that I hadn’t come down, I had come all the way up from the bottom! Was I a goat? No, if I had been able to see more clearly what I had been coming up, I wouldn’t have tried! I felt like a muppet for having made it within 10m of the top, but as I said, it may as well have been a mile with my visibility, available secure hand holds, and my condition.

After a warm up with hot drink and a jacket, I was fit to walk the short distance back to camp.

A special thanks to everybody involved in the chain – the ACR service who took the signal, New Zealand Commination’s, Taupo Police and the Greenlea trust.

Words of wisdom

I had the ACR in a front pocket where I would easily get to it with one hand – thinking that if I ever needed it, it would be because of a fall, in which case I might be separated from my pack. That proved to be a saving decision.

Thank you note

Rescue location

Kaimanawa

Rescue team

Other

ResQLink™

Go to product detailsOut of stock