Lives saved

1

Climbing

Mountain

Lost

Grindelwald, Switzerland

46.624164°N, 8.0413962°E

Posted on January 29, 2019 by Sean

What happened?

It doesn’t take much for things to go wrong on the Eiger… I left the car well before dawn, following the trail and via ferrata to the Ostegg Hut. From there, the climb to the ridge crest is a mixture of rotten, steep rock bands and ledges covered in outward-sloping rubble, and the route stitches together corners and chimneys through the bands via traverses on the rubble. I some other climbers just at the ridge crest, where I felt my first sun of the day, and also realized that I had a serious task ahead of me to reach the Mitteleggi Hut and the Eiger beyond. The ridge below the hut is very long, with a narrow crest, many gendarmes and undulations, a sheer left side, and a right side made of the insecure garbage I had just climbed.

After an initial preamble, the crest rises in a large, steep step. The climb was complicated and fairly stressful, but I made steady upward progress until shortly below the ridge, where I was stopped by a smooth, steep band with no obvious breaks. After a good 10 minutes of careful experiment and retreat, I found a combination of nasty little outward-sloping ledges secure enough to get me past the impasse; above, easier climbing led back to the crest. I continued making steady, patient progress, focused but not frightened, and was eventually rewarded with a view of the Eiger’s famous snow-clad North Face, rising above a gap in a southward bend with a prominent window. It still looked terribly far away, and I had not even reached the start of the official Mitteleggi “route,” but the weather remained perfect, and based on my phone’s GPS, I was moving fast enough.

Ahead, I saw another intimidating-looking step, whose right side looked unfortunately steep. When I reached the notch at its base, the crest looked like it would require some intimidatingly-steep face climbing. I wanted to avoid that if possible, so, with the right side steeper than usual, I explored left, finding the beginning of an apparently-usable route. The route slowly got more difficult, until I found myself carefully edging up an awkwardly-sloping ledge, ending at a vertical dihedral. It was hard climbing, but between stems and hand jams, I felt reasonably secure on the poor rock, and was making steady cautious upward progress. Suddenly, a foothold broke. I was climbing with enough points of contact not to immediately fall, but in that adrenaline-filled moment of up-or-down, I chose up. I eventually reached a stance at a small alcove below a roof, and could finally stop to calm myself and assess my options. I was not at all confident that I could reverse the dihedral I had just climbed. Going left around the roof would require climbing a steep bulge into the unknown: even if nothing broke, I would be committed and did not know what lay above. Going right seemed a bit more promising, with a decent-looking hand crack leading up the sloping face starting just out of reach. I made a few tentative tries, but could not find a secure series of moves to reach the crack.

I returned to my stance, made myself as secure as possible, and tried to calm myself as I considered my options. I repeatedly considered my two options — up and right or back down — hoping that with steadier nerves I would find the confidence to try one. After about a half-hour of debate, I was no more confident in a solution, and was getting uncomfortable wedging my back into the alcove while staring out at the glaciers far below.

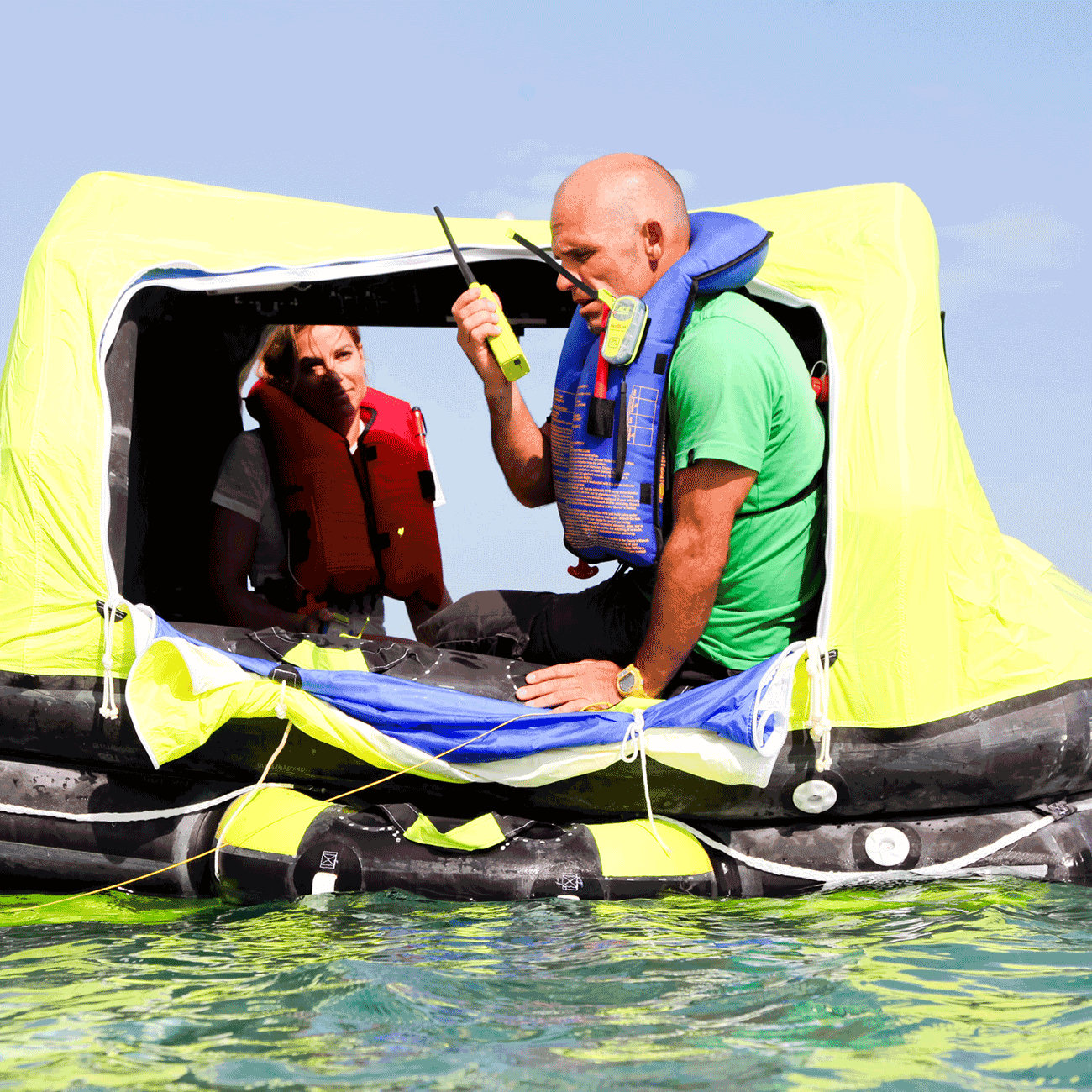

I had hoped never to do this, but I pulled out the rescue beacon I had been carrying for a couple of seasons, read the instructions, waited for the light to blink, and pressed the button. Now there was nothing to do but wait. I slotted my ice tool into a crack behind me, hung my pack on it, and admired the Fiescherhorn across the Ischmeer while listening for helicopters. They are not uncommon in the Alps, carrying sightseers, stocking huts, or simply patrolling. After an hour or two waiting, I heard one pass unusually close a couple of times, and got ready to make the “yes” sign should it come into view. Unfortunately it never did, and I continued to wait.

I thought it likely that any rescuers had been thrown off by a bad GPS bounce, and were unlikely to fly close enough to my perch to see me. By now I had concluded that the route followed the ridge crest — perhaps that step had been easier than I thought — so I began listening carefully for the two parties I had passed. A couple hours later, I heard someone above, and called out to them in probably incorrect German. They eventually called back, but of course they could not see me, as I was hidden beneath the overhang. Thinking for a moment, I called “stein!” (rock), then threw a couple of the many nearby loose rocks in gentle arcs away from me, so they would hit the face lower down, and hopefully get the party’s attention. After a couple tries, they figured out what I was doing, and one of them shouted “Ein stein!” (one more). I did so, and after a bit they continued up the ridge, with one calling down “help is on the way” in accented English.

Sure enough, after a bit more waiting, I heard a helicopter coming closer than before. It came across the face from the left, and I stood to raise both arms indicating than I needed help. They spotted me and approached head-on until I could clearly make out the pilot and passenger. When they next returned, I heard them insert a party above me, who built an anchor, then one lowered the other until he came around to the right of the overhang. He spent a few minutes knocking at the face to my left, looking for a solid bolt placement, then drilled and placed a long bolt, clipped in, and untied from the rope above.

I had put on my pack at some point, and he wrapped some sort of canvas full body harness around both me and the pack, clipped it in front, and tied me into the anchor. After another few minutes passed, the helicopter returned, and short-hauled both of us back down to the Ostegg Hut. From there, I was able to hike back down to Grindelwald.

Words of wisdom

You’re never completely safe in the mountains, but don’t climb up anything you can’t climb down.

Thank you note

The satellite beacon worked perfectly. As for the GPS, there’s nothing to be done about it in complex mountain terrain.

Rescue location

Grindelwald, Switzerland

Rescue team

Local Search and Rescue

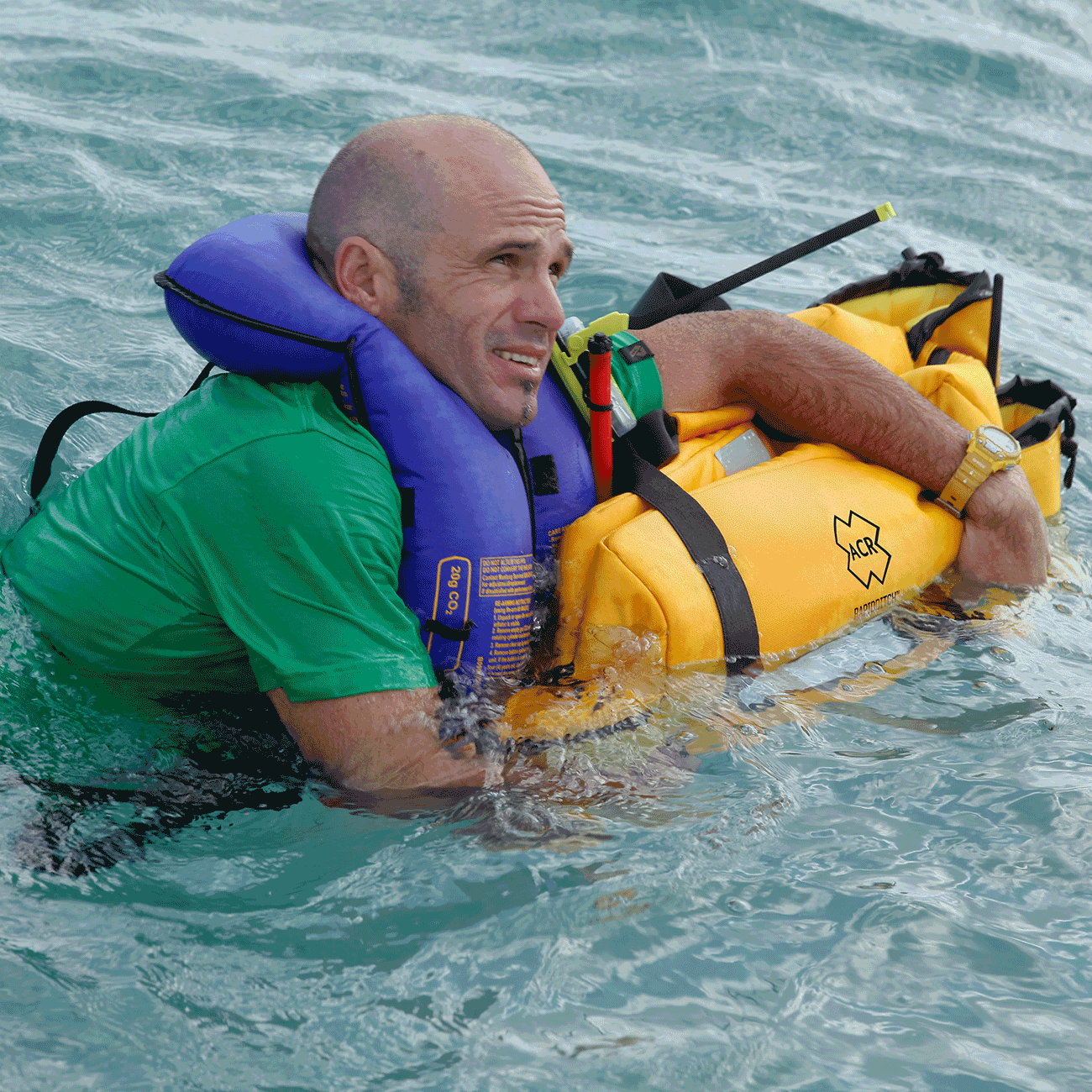

ResQLink™

Go to product detailsOut of stock